Story by Ian Baker

The disability support service AQA Qualcare was established by a talented trio from diverse backgrounds who served distinct but compatible motives.

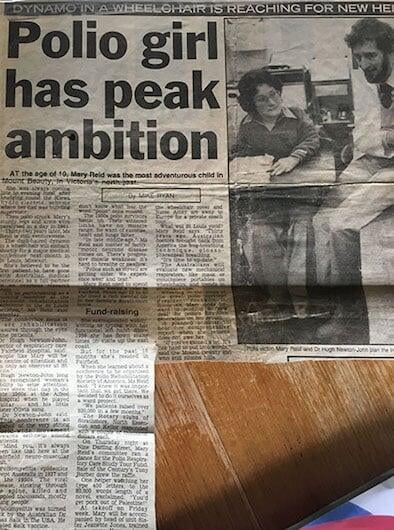

Spearheading the project was Mary Reid, a polio survivor who had grown up in Mt Beauty, at the foot of Mt Bogong in north-eastern Victoria.

Reid had the most to gain personally from the initiative, seeing it as a path to liberation from her profound dependence on her family, when she lived at Mt Beauty, and on staff at the Fairfield Infectious Diseases Hospital, where she had stayed when in Melbourne.

Known in childhood for her energy and buoyant spirit, she had fallen ill with polio a few days before her 11th birthday.

“It struck me pretty quickly,” Reid says of the infection. “I lost the use of my arms and legs. I had to be put in the iron lung. I remember that I was very frightened going into the box.”

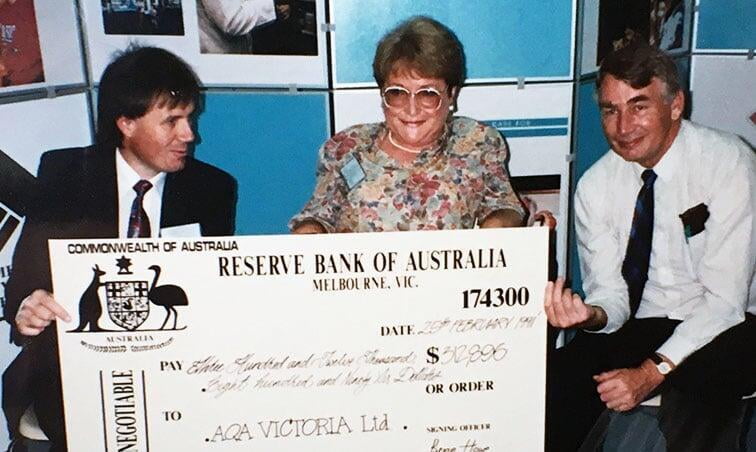

Reid never regained movement in her legs but recovered limited use of one arm. She had lived with her paralysis for nearly 40 years by the time her relentless lobbying led federal minister for health and community services Brian Howe to launch the Qualcare Service Respite Program in February 1991.

Interviewed at a Melbourne retirement home, Reid explains that she had followed for decades the development of assistance for fellow polio survivors in Australia and overseas, and had travelled to United States cities and London in the course of her research.

“A pilot program for attendant care was just starting in Sydney,” she recalls of her decision to agitate for a Victorian service.

“I thought this attendant care business sounded pretty good, and that with that I could do lots of things.”

Something completely different

Engineering the project was Fiona Gologranc, who joined AQA Victoria in 1990 under her maiden name of Fiona Hopkins. After completing high school and business college, Gologranc had spent eight years in sales and marketing support with a Melbourne importer of machine tools.

“It was a very cutthroat type of business setting,” recalls Gologranc, who would go on to become AQA finance manager. “I felt a bit burnt out and wanted to do something that had more meaning.

“AQA had advertised for someone to provide administrative support for their lobbyist, who was trying to get an interesting program off the ground. I thought that would work for me.”

Challenged to do more

Catalysing the project was Ian Bennett, born near the goldfields city of Ballarat, northwest of Melbourne, who had been living with incomplete quadriplegia from a car crash at 21. Bennett had retained significant control of all limbs and could walk with the help of a stick.

Recruited to AQA at a time when it was a branch office of the Sydney-based Australian Quadriplegic Association, and operating mainly as a sheltered workshop, Bennett had overseen its incorporation in 1987 and had been appointed CEO.

After taking the helm of the newly independent non-profit enterprise he had broadened its mission, initiating a peer support program for people with spinal cord injuries and accumulating a membership that he served with a newsletter.

Early in his tenure, he had been challenged by a young woman with quadriplegia whom he had visited at the nursing home where she lived.

“She said: ‘What can you do for me?’” Bennett, then in his mid-30s, recalls. “I said, ‘Not a lot right now.’

“And I started to think about what AQA might do for someone like her.

“She didn’t want to work – didn’t even know if she could work. What she said she wanted, in an ideal world, was to live independently.”

Favourable climate

Bennett was aware that he had a relevant connection in Reid, who had been assessing the costs of providing attendant care at home for people with severe physical disabilities. Reid’s study had operated autonomously, but from a former AQA office in Northcote and supported by government funding channelled through AQA.

He invited Reid to join AQA Victoria, develop a proposal for an attendant care service, and seek financial support for it.

The political climate was favourable. A ground-breaking review had recently led the Australian government to pass a Disability Services Act, which became effective in June 1987. The legislation sought to improve opportunities for people with disabilities, in part through helping them take more control of where and how they lived.

Bennett secured a small grant that supported Reid’s work, and employed Gologranc to assist her.

A grassroots organisation

“The organisation was three years old at that point,” says Gologranc, describing the scene she settled into at 70 Station Street, Fairfield. “I came in from a very swish, corporate, money-no-object type of background.

“I walked in to be given a sheet of Con-Tact adhesive vinyl, and was told to try and make this bookshelf work with some Con-Tact on it. Some of the chairs only had three legs. It was a very donated-furniture, grassroots organisation. Nothing matched. But people were there for the right reasons, and trying to get some exciting programs up and running.”

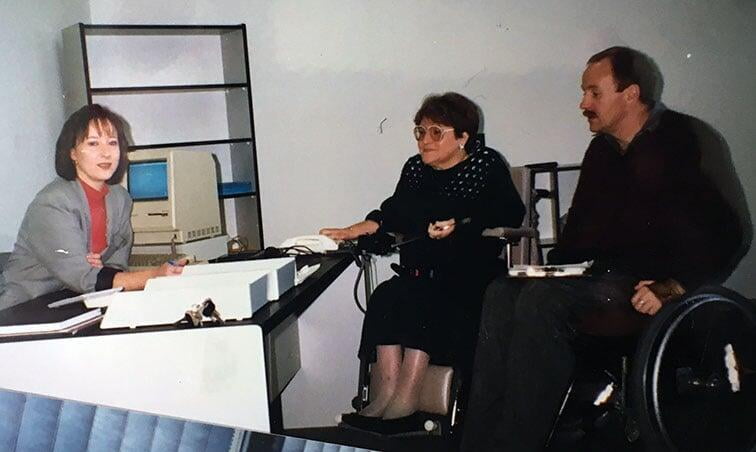

From Bennett’s perspective, the division of labour in Reid’s small team was sharp.

“Mary was the front-person, the lobbyist, and she did a good job,” he says.

“Fiona was the nuts and bolts behind it. She did all the submission writing, as well as acting as Mary’s personal carer.”

Strength of will

However, Gologranc emphasises that it was only through Reid’s dedication and strength of will that their joint efforts succeeded.

“Mary was not a professional lobbyist,” she notes. “She was a very determined, independent person with a severe disability.

“She was a driven woman, and our program wouldn’t have got off the ground without her.

“She had been around Fairfield Hospital and knew people using iron lungs who had been institutionalised their whole lives. She was all about empowering people, and trying to get people out of institutions and living in the community.

“I was really the administrative sidecar to Mary.

“The submissions were built directly on what Mary could tell me from her prior knowledge and from her research and contacts.”

Travels to Canberra

Gologranc undertook a series of trips to Canberra with Reid, meeting politicians and bureaucrats. The duo focused on developing a service through which trained carers could bring respite to people who were supported by family members at home.

Reid says she had thought that the respite service might work with 10 clients initially. She says she was told in a phone call from Canberra that she needed a bigger number, and was taken aback when her impromptu suggestion of 40 was accepted immediately.

“We kept haggling Brian Howe, who was health minister and whose electorate happened to cover Northcote and Fairfield,” she remembers.

“First thing I knew, someone from his office rang me and said our program would be funded and there would be a budget for a set number of places.

“It was agreed that AQA would deliver that funding and I had to choose a name.

“I said, ‘Well I want Quality Care, because we should do quality care only from here.’

“A guy in the AQA office who worked on the phones said: ‘That’s a dorky name.’

“I said: ‘Well, that’s what it needs to be.’ So we went with Qualcare.”

Gologranc confirms: “The Qualcare Service Respite Program, which was the foundation of AQA Qualcare, was about providing respite care for a group of 40 people we had identified, half in the city and half in the country.

“It became quite a political thing – we had to try to find clients in the right electorates, although we weren’t driven just by that criterion.

“The structure we set up to operate the respite service allowed AQA Qualcare to accept other clients, and these came to us with funding from sources such as the newly formed Transport Accident Commission.”

Honoured for service

Reid stayed with AQA for several years after the Qualcare program was launched, drawing on her lived experience to develop guidelines for carers and build training programs.

“This was a time when the personal narrative carried significant weight,” observes Peter Trethewey, in that period a social worker with the spinal unit at Austin Hospital. Trethewey was appointed CEO of AQA Victoria in 2007.

“The fledgling AQA was certainly at the cutting edge of shaping what attendant care would look like, in a context of de-institutionalisation,” Trethewey says.

“People like Mary with her energy and her research of emerging community-based options for care were formidable.

“This was also an early expression of what has become AQA’s DNA, and in particular of its building individually tailored experiences that empower its clients.”

In 2006, Reid was awarded the Medal of the Order of Australia for her service to people with disabilities. The citation highlighted her work “as a contributor to the advancement of attendant care services to allow independent living.”

“I feel proud that I was able to do the work that I did,” she says, “and that I was able to achieve a lot more than I thought I would. I got to learn quickly that you need to be persistent, and I have been dogged in my persistency.”

At the end of 2019, nearly 29 years after the program began, AQA was supplying individualised supports to about 240 clients living with complex physical disability, through the dedication of more than 400 disability support workers.

- November 30, 2020