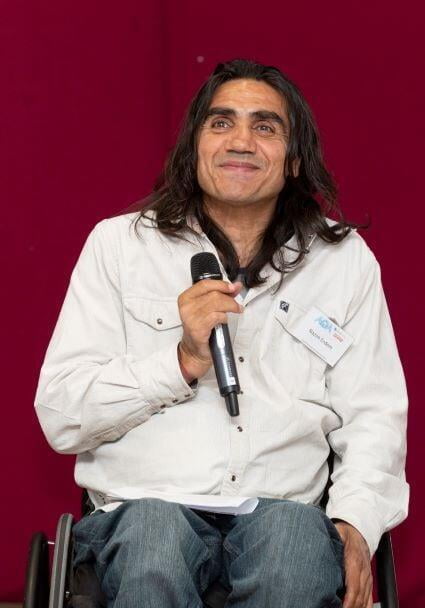

Story by Ian Baker

When founding CEO Ian Bennett formed AQA Victoria in 1987, he formed it to save the jobs of his colleagues.

Alongside other people with quadriplegia, Bennet had been working for the Sydney-based Australian Quadriplegic Association from an office in the Melbourne suburb of Fairfield.

Sydney decided to close the Melbourne office. Bennett, who had been its book-keeper, fought to keep it open, driving his own car 880km north on the Hume Highway to plead with the CEO at the time, Bill Saville.

“My wife supported me,” Bennett recalls. “I told her: ‘I have to do this.’ She asked why. I said: ‘I’m an incomplete quad. If I was complete, I would be the same as about four of those guys who are working in the office. I have to give this a bash, for them.’

“I knew they were getting a lot of enjoyment out of working in the office. And there was no prospect of them getting any other work.”

The opportunity to contribute

Bennett’s rescue mission succeeded. Saville put him in charge, and gave him six months to show that the office could support itself. Having shown that, he was given only a further three months to sever formal ties with Sydney and go it alone. He formed AQA Victoria Limited, a not-for-profit company.

Its Annual Report explained in 1991:

“AQA Victoria Limited works with the objective of ensuring that physically disabled people have the opportunity to live and work as a contributing member of our community.”

Bennett would lead AQA for the next 20 years. Keeping open the doors would remain a primary focus. The company had a contract to compile traffic accident statistics for the State Government authority VicRoads, and when that work dwindled Bennett built a desktop publishing business, Copies Plus. An attendant care business, AQA Qualcare, opened in 1991 and grew steadily.

Revenue from the successful businesses, and from a government grant that subsidized the employment of people with disabilities, funded an information service and newsletter for people with spinal cord injuries, and the coordinating of AQA’s peer-support outreach to people recently injured.

Tragedy and misadventure

Bennett was a country boy whose can-do attitude had grown from tragedy and misadventure. He had been brought up in Newlyn, a small town near Ballarat. His mother had died when he was 11 months old, and his grandparents had cared for him and for his brother, who was two

“My mother had post-natal depression,” Bennett reveals. “I learned eventually that she had shot herself, and my father found her. My father had come home from the war and built a trucking business and a sawmill. He had a nervous breakdown, became an alcoholic, and did a bit of work around the district. My grandparents, who were in their 60s, took on my brother and me, and tried to keep my father on track.”

When Bennett was 15 his grandfather died, and he moved in with an aunt – “a fantastic lady” – in Ballarat. In 1975, when he was 21, he was asleep in the back of a panel van when it crashed. He emerged from 16 months of rehabilitation with incomplete quadriplegia: he could use his arms and hands and could walk, but with diminished strength and control.

He was a qualified toolmaker and had worked laying carpet. After his accident, acting on a chance opportunity, he bought a ride-on lawnmower and started a mowing and landscaping business. Then he moved the business to Melbourne.

“Eight years later I had about five guys working with me,” he remembers. “At the same time I was studying book-keeping and accounting. I didn’t like it, but I knew that to get on I had to do something that was indoors and sensible. I also had a partnership in a service station, and I did the books there.”

Need for support

Bennett was recruited to AQA’s forerunner, initially on a voluntary basis, when playing wheelchair sport. After his rescue mission established AQA Victoria, he had planned to move on. Persuaded to stay, he was appointed CEO and remained at the helm until he stepped away in 2007.

At the time he left, AQA Qualcare employed about 480 carers and had been adding about 20 clients a year, he says. The VicRoads contract was a distant memory, and Copies Plus had been closed. The newsletter and information service had endured, with its reach extended to Tasmania, and peer support had become a core service that was delivered pro bono.

Although he had saved AQA for the sake of his co-workers with quadriplegia, Bennett had long understood that demand for the subsidized jobs it could offer was low.

“It was very hard to find people,” he says. “We were looking for someone to work, all the time.

“But people with spinal cord injuries still needed support.”

Popular appointment

Bennett’s successor, Peter Trethewey, was a known face at AQA long before his appointment, having joined AQA’s Board of Directors in 1992 and served until 2004, for four years as chair. He was a popular choice. Bennett recalls himself as having proposed to Trethewey that he apply to become CEO. Trethewey had also been sounded out by the serving Board chair.

Bennett’s Executive Assistant, Robyn Canning, tells of having discussed the question of Bennett’s successor informally with fellow long-serving employee Fiona Gologranc, at the time Accounts Supervisor. “Fiona and I said to each other: ‘Wouldn’t it be great if Peter went for the job!’ Never thinking he would,” Canning says. She would remain as Executive Assistant under Trethewey.

Trethewey’s decision to run AQA was not obviously prudent. After two years in a graduate job with a family support organisation, he had stepped sideways to a bottom-rung social-work role with the Spinal Injuries Unit at the Austin Hospital. He had spent the past 19 years there: 12 of them in successively senior clinical posts, and seven leading the unit, by then named the Victorian Spinal Cord Service, as Business Manager.

“I had heaps of people who looked at me and said, ‘What on earth are you doing? You’re talking about moving to a big position in a small organisation, without any support,” Trethewey acknowledges.

“There has been a bit of a theme in my working life where I have got to a point of change, and then a decision has appealed to me that doesn’t quite make sense to the people around me – in terms of the career trajectory that most people would have followed.”

Against ridiculous odds

What appealed was the opportunity to sustain a direct connection with serving people who had sustained spinal cord injuries, rather than ascending in the public health bureaucracy to more remote roles. There was also the contribution AQA was making with its peer support program, whose benefits Trethewey had seen close-up in the course of his social work.

And there was the sense that he could pursue from a different perspective his objective when running the Spinal Cord Service, which he describes as influencing a health system to help people create a new and meaningful normal in extremely abnormal – and adverse – circumstances.

“The capacity of human beings to find a way through the physical and psychological hailstorm of spinal cord injury and rehabilitation, and find some meaning and a new normal, I find remarkable,” he says, talking of what he has drawn from his professional life.

“Being around that is affirming to me. And getting to know it so that you feel like you can contribute to it is remarkable.

“The resilience of human beings I find really interesting. The people I respect most are people who have been resilient, and persistent, and values-driven, and goals-driven, against ridiculous odds.”

Goodbye sheltered workshop

An early challenge for Trethewey, after he accepted appointment to CEO, was a foreshadowed change to how funding was calculated for enterprises that employed workers with disabilities.

His predecessor had persuaded Australian Government bureaucrats that they should subsidise AQA to employ people with spinal cord injury who were producing its newsletter, NewsLink. Those people also led AQA’s peer support outreach. But a change in the terms of the subsidy was expected to cut it dramatically – essentially because its recipients were performing too well – and Trethewey’s first goal was to sustain that outreach, which he had seen as potentially AQA’s signature offering.

In replacing indirect support for AQA’s peer-support program with direct support, from private patrons and the Department of Human Services, Trethewey severed AQA’s final tether to the sheltered-workshop model upon which it had been founded. And with that break came an opportunity to reframe AQA’s outlook.

“If I were to challenge our history as an organisation,” Trethewey says, “my challenge would be to the proposition that simply employing people with a spinal cord injury was an outcome. Full stop. But that is where we began, and that is how the community saw things.

“To that, I would say: Why? What are these people doing? What are you hoping to achieve with them as a resource? That is where we are now.

“You can also look at the location of that achievement – where the success happens.

“Early on, success for AQA was having people doing things in the office.

“Now, the office might be a base – but our work is about what happens out there, in the community. That is where success is going to come from for us.”

The organisation that left home

Trethewey’s long familiarity with the public health system has also helped him foster at AQA a more mature relationship to his former department, the Spinal Cord Service.

It was notionally under the authority of the service that AQA had begun and continued its peer-support outreach to recently injured people. When founding peer support coordinator Greg Kidd sought to extend that outreach beyond metropolitan Melbourne, he had done so by attending regional spinal injury clinics.

“For a range of reasons, I was desperately keen that AQA establish its identity outside its connection with Austin Health,” Trethewey says.

“To adopt a metaphor from family therapy, we needed to be the organisation that confidently left home.

“For example, I was really clear that our peer support regional networks needed to grow beyond that connection with the hospital system.

“Hospital staff talk about patients and ex-patients, and it is tempting for them to see people such as our peer support volunteers and those they mentor as ex-patients, primarily. But these guys have so much more to offer than ‘you used to be a patient’ – they have all the things they have learned from their lived experience.

“We needed to recognise that if we could do it well, we had a value outside the permissions of the public health service, or the description ex-patient.

“For the past five years we’ve been working to recognise that value in what we have, and how we can present that to the community.”

Supporting life goals through NDIS

Trethewey sees great promise for AQA in the philosophy of the National Disability Insurance Scheme. While open-eyed to its shortcomings, he views the scheme’s introduction as a turning point in the relation of people with disabilities to the funding available for their support.

“Organisations like ours have effectively been constrained by what our clients and community had permission to pay for with their funding,” he points out.

“For example, AQA Qualcare was born out of deinstitutionalisation. That took off partly because it was the right thing to do, but mostly because it cut costs for governments.

“That business grew, and attendant care programs delivered to people such as our clients the money to buy attendant care services – and only those services.”

The NDIS had brought with it a dramatically different approach, where the provision of funding was justified as an investment in outcomes – in a participant’s progress towards reaching his or her goals.

“The prospect is that an informed client and community can secure the services that they value as supporting their life goals – rather than just the services they have been prescribed,” Trethewey explains.

“If at AQA we can reimagine our personal care, community access supports, and other offerings, not as the only services that the person is funded to purchase, but as services that support the client in their aspiration to live an enjoyable life, then our mature business has a place.

“We are delivering a service to you because it has a value in the life that you are attempting to construct.

“And then, AQA might have an extraordinary capacity to deliver something else into your life, that would help you achieve your goals. That’s the opportunity we’ve got.”

- June 30, 2020